MCTS applied to card games

2021-08-13 | Blog Article

Objective

At Flybot Pte Ltd, we wanted to have a robot-player that can play several rounds of some of our card games (such as big-two) at a decent level.

The main goal of this robot-player was to take over an AFK player for instance.

We are considering using it for an offline mode with different level of difficulty.

Vocabulary:

big-two: popular Chinese Card game (锄大地)AIorrobot: refer to a robot-player in the card game.

2 approaches were used:

- MCTS

- Domain knowledge

The repositories are closed-source because private to Flybot Pte. Ltd. The approaches used are generic enough so they can be applied to any kind of games.

In this article, I will explain the general principle of MCTS applied to our specific case of big-two.

MCTS theory

What is MCTS

Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) is an important algorithm behind many major successes of recent AI applications such as AlphaGo’s striking showdown in 2016.

Essentially, MCTS uses Monte Carlo simulation to accumulate value estimates to guide towards highly rewarding trajectories in the search tree. In other words, MCTS pays more attention to nodes that are more promising, so it avoids having to brute force all possibilities which is impractical to do.

At its core, MCTS consists of repeated iterations (ideally infinite, in practice constrained by computing time and resources) of 4 steps: selection, expansion, simulation and update.

For more information, this MCTS article explains the concept very well.

MCTS applied to big-two

MCTS algorithm works very well on deterministic games with perfect information. In other words, games in which each player perfectly knows the current state of the game and there are no chance events (e.g. draw a card from a deck, dice rolling) during the game.

However, there are a lot of games in which there is not one or both of the two components: these types of games are called stochastic (chance events) and games with imperfect information (partial observability of states).

Thus, in big-two, we don’t know the cards of the other players, so it is a game with imperfect information (more info in this paper).

So we can apply the MCTS to big-two but we will need to do 1 of the 2 at least:

- Pre-select moves by filtering the dumb moves and establish a game-plan

- access to hidden information (the other player’s hand). This method is called Determinization or also Perfect Information Monte Carlo Sampling.

MCTS implementation

Tree representation

Our tree representation looks like this:

{:S0 {::sut/visits 11 ::sut/score [7 3] ::sut/chldn [:S1 :S2]}

:S1 {::sut/visits 5 ::sut/score [7 3] ::sut/chldn [:S3 :S4]}

:S3 {::sut/visits 1 ::sut/score [7 3]}}

In the big-two case, S0 is the init-state, S1 and S2 are the children states of S0.

S1 is the new state after a possible play is played

S2 is the new state if another possible play is played etc.

S1 is a key of the tree map so it means it has been explored before to run simulations.

S1 has been selected 5 times.

S2 has never been explored before so it does not appear as a key.

In games when only the win matters (not the score), you could just use something like ::sut/wins.

Selection

To select the child we want to run simulation from, we proceed like this:

- If some children have not been explored yet, we select randomly one of them

- If all children have been explored already, we use the UCT to determine the child we select.

UCT is the UCB (Upper Confidence Bound 1) applied to trees. It provides a way to balance exploration/exploitation. You can read more about it in this article.

In the algorithm behind AlphaGo, a UCB based policy is used. More specifically, each node has an associated UCB value and during selection we always chose the child node with the highest UCB value.

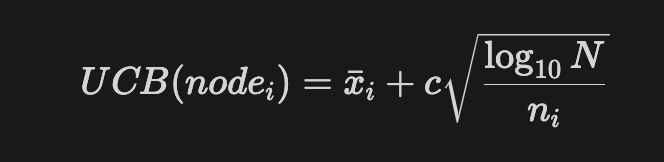

The UCB1 formula is the following:

With

xithe mean node value,nithe number of visits of nodei,Nthe number of visits of the parent node.

The equation includes the 2 following components:

The first part of the equation is the exploitation based on the optimism in the fact of uncertainty.

The second part of the equation is the exploration that allows the search to go through a very rarely visited branch from time to time to see if some good plays might be hidden there.

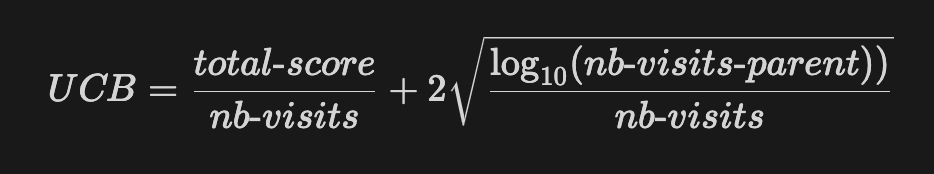

In the big-two case, the exploitation is the total number of points divided by the number of visits of the node. For every simulation of the games, we add up the number of points the AI has made. We want the average points per game simulation so we divide by the number of times we have visited the node.

In the big-two case, the exploration considers the number of visits of the parent node (previous state of the game) and the number of visits of the current node (current state of the game). The more we visit the parent without visiting the specific child the bigger the exploration term becomes. Thus, if we have not visited a child for a long time, since we take the log10 of N, this term becomes dominant and the child will be visited once more.

The coefficient c, called confidence value, allows us to change the proportion of exploration we want.

To recap, The UCB will often return the state that led to the most points in the past simulation. However, from time to time, it will explore and return a child that did not lead to good reward in the past but that might lead to a stronger play.

The formula applied to big-two is the following:

Expansion

This step just consists in adding the new selected child to the tree.

In the big-two case, the newly selected state is added to the tree.

Simulation

For a given node (state), we run several games with everybody playing random moves and we evaluate the total score of the AI. The total amount of points taken from all the simulations is taken into account in the UCT formula explained above.

We do not consider the win because what matters in big-two, more than winning the game, is to score a lot of points (cards remaining in opponents hands) to make more money. Sometimes, it is even better to lose the game as long as the other losers have a lot of cards left in their hands. The win matters for your position in the next round however.

Update

After all the simulations are done, we back-propagate all the rewards (sum up the scores of each simulation) to the branch nodes.

MCTS Iteration

We call MCTS iteration the 4 steps described above: expand->select->simulate->update

We run those 4 steps several times to have a tree that shows the path that has the most chance to lead to the best reward (highest score).

So, for each AI move, we run several MCTS iterations to build a good tree.

The more iterations we run, the more accurate the tree is but also the bigger the computing time.

MCTS properties

We have 2 properties that can be changed:

nb-rollouts: number of simulations per mcts iteration.budget: number of mcts iterations (tree growth)

MCTS applied to a game with more than 2 players

Having more than 2 players (4 in big-two for instance) makes the process more complex as we need to consider the score of all the players. The default way of handling this case, is to back-propagate all the players scores after different simulations. Then, each robot (position) plays to maximize their score. The UCB value will be computed for the score of the concerned robot.

Caching

By caching the function that returns the possible children states, we don’t have to rerun that logic when we are visiting a similar node. The node could have been visited during the simulation of another player before so it saves time.

By caching the sample function, we do not simulate the same state again. Some states might have been simulated by players before during their mcts iterations. This allows us to go directly a level down the tree without simulating the state again and reusing the rewards back-propagated by a previous move.

Performance issue

In Clojure, even with caching, I was not able to run a full game because it was too slow, especially at the beginning of the game which can contain hundreds of different possible moves.

For {:nb-rollouts 10 :budget 30} (10 simulations per state and 30 iterations of mcts), the first move can take more than a minute to compute.

As a workaround, I had the idea of using MCTS only if a few cards are remaining in the player's hands so at least the branches are not that big in the tree. I had decent results in Clojure for big-two.

For {:nb-rollouts 10 :budget 30 :max-cards 16} (16 total cards remaining), in Clojure, it takes less than 3 seconds.

Because of this problem, I worked on a big-two AI that only uses the domain knowledge to play.

Domain Knowledge

The problem with MCTS is that even if we don’t brute force all the possibilities, the computing time is still too big if we want to build the tree using random moves.

Most of the possible plays are dumb. Most of the time, we won’t break a fiver just to cover a single card for instance. In case there are no cards on table, we won’t care about having a branch for all the singles if we can play fivers. There are many situations like this. There are lots of branches we don’t need to explore at all.

As a human player, we always have a game-plan, meaning we arrange our cards in our hands with some combinations we want to play if possible and the combination we don’t want to “break".

We can use this game-plan as an alternative to MCTS, at least for the first moves of the games.

The details of this game-plan are confidential for obvious reasons.

Conclusion

Having an hybrid approach, meaning using a game-plan for the first moves of the game when the possible plays are too numerous, and then use MCTS at the end of the game allowed us to have a decent AI we can use.

As of the time I write this article, the implementation is being tested (as part of a bigger system) and not yet in production.

Contribute

Found any typo, errors or parts that need clarification? Feel free to raise a PR on the GitHub repo and become a contributor.